Attitude Formation: Cultural Influences on Attitude Toward LGBT Individuals

Abstract

This study seeks to better understand the reasons upon which college students

base their opinions of LGBT people. The hypothesis states that college students

at a midwestern university will base their attitude towards the LGBT community

more on their friends’ attitude of the LGBT community than on their mother’s

attitude or their father’s attitude. One hundred fifty one students from a

midwestern university participated in the study. A 55-item questionnaire was

compiled using questions from the Components of Attitudes Toward Homosexuality

scale (Lamar & Kite, 1998). There were three independent variables (similarity

to father, similarity to mother, similarity to friends) and seven dependent

variables (6 sub-scores and an aggregate score). In the future, this work can

serve as the starting block for research into the effects of attitude formation;

it would be interesting to look for patterns in the behavior of those who form

their attitudes in one way or another.

Keywords: sexual orientation,

attitude, contact hypothesis

“For social scientists, the opportunity

to serve in a life-giving purpose is a humanist challenge of rare distinction.”

(King, 1967, par. 3). Martin Luther King, Jr. articulated this phrase as a

call-to-arms for social scientists and his words ring true today. Yet, the

struggle has transitioned from one minority group to another. Society has

entered another area of social justice, and psychology sits at the center of the

issue. There are multiple facts that call attention to LGBT (lesbian, gay,

bisexual, transgender) concerns and rights in our society:

§

3.5% of Americans classify as LGBT (Stark, 2012)

§

48% of Americans oppose same-sex marriage today, but 68% of Americans opposed

same sex marriage in 1996 (Stark, 2012)

§

About one third of American LGBT youth have attempted to commit suicide (Robin,

Brener, Donahue, Hack, Hale, & Goodenow, 2002)

§

Over 80% of LGBT students have reported that faculty and staff make no effort to

stop verbal abuse and harassment in the classroom (GLSEN, 2003)

§

In 2005, more than 1 in every 10 cases of hate crimes was related to sexual

minority status (Robin et al., 2002)

Although there are a number of interesting research questions relating to the

LGBT community, one of the most important is the way that outside influences

affect the formation of one’s attitude toward the LGBT community. This study

seeks to better understand the reasons upon which college students base their

opinions of LGBT people. Are their opinions predicated on the influence of

parents, the influence of friends, their ethnicity, or another factor? In order

to change behavior, we must first understand thoughts and the origin of

thoughts. “Thoughts become feelings, feelings become attitude, and attitude

becomes behavior” (J.L. Kemp, personal communication, September 24, 2012).

Attitude is defined as the “positive or negative evaluations of humans, objects,

or ideas, which can be reflected in an individual’s cognitions, sensibilities,

and behaviors (Cao, Wang, & Gao, 2010, p. 722). In contrast, to understand

attitude, we must first discover its source; only then, we can narrow down

influences and become more specific. For instance, if a participant’s attitude

is predicated on parents’ beliefs, the next step is to discover the basis of

parental beliefs (religiosity, homophobia,

their parents’ beliefs, etc.). This

study aims to determine that first step and provoke future research among

college students.

Background: Nature vs. Nurture

The most basic question in the discourse on homosexuality is whether or not it

is “natural;” in other words, are people gay/lesbian because they were made that

way, or because they choose to be that way. Past research (Sarantakos, 1998) has

characterized this debate as essentialists versus social constructionists.

Essentialists believe that homosexuality comes from a fundamental component of

one’s identity and that it is unchangeable and fixed. Further, they posit that

homosexuals ‘come out’ when they accept themselves as gay or lesbian. Finally,

they support their argument by referencing the ineffectiveness of reparative

therapy (designed to adjust homosexuals back to the normal state of

heterosexuality). In fact, reparative therapy has increased the likelihood of

clients attempting suicide (Schidlo & Schoredor, 2002).

In contrast, social constructionists posit that one’s sexual identity is

not a fixed element of personality and that “what seems to be a self-discovery

is better considered as self-construction” (Sarantakos, 1998, p. 23). In

addition, they strongly suggest that sexuality constantly shifts and adjusts

throughout life, which would support their position of sexuality as a social

construct. Neither theory describes homosexuality as an illegitimate component

of personality; they simply conflict on the consistency and the depth of

homosexuality. A significant factor in one’s attitude towards LGBT people has

been between those who see it as a natural component of personality versus those

who see it as an unnatural component. This distinction strongly affects one’s

perception and attitude towards homosexuals.

Generational Differences: Parents’ influence vs. Friends’ Influence

As indicated by a CBS News poll in May (Reals, 2012), there is a strongly

defined generational gap when considering attitudes towards the LGBT community.

On average, 38% of people stated that same-sex couples should be allowed to

marry, but when we striate the survey by age, we see a huge shift. In people

aged 18-44, 53% believed that same-sex couples should be allowed to marry; in

people aged 45 and over, only 24% believed that same-sex couples should be

allowed to marry. Interestingly enough, the 18-44 group had an almost identical

approval of same-sex marriage as did proclaimed Democrats when considering the

poll’s sampling error: 53% and 58%, respectively. This survey strongly indicates

that there may be a strong difference between what participants hear at home and

what they hear in other places. Therefore, it will be interesting to study the

effect of parental influence on students’ attitudes towards LGBT people.

In the same manner, this study will measure the effect of friends’

influence on students’ attitudes towards LGBT persons. College students often

move away from home and grow independent of their parents at this time, often

spending much more time around other college students. This paper focuses on

college students, because of the unique interaction between two variables: (a)

their independence as critically thinking adults versus the influence of their

parents; and (b) the clash between two very strong influences: parental

influences and friend influences. The generational gap is also unique to this

study because of the historical context. From 1947 to 1997, a comprehensive

analysis of Time and News Week magazine articles by Bennet found that “nearly

every article was resoundingly critical of gays and lesbians both in language

and in content” (Blackwell, 2008, p. 653). Eight years ago, a national survey (Capehart,

2012) found that 31% of respondents stated that same-sex marriage should be

legal, while 60% stated that it should be illegal. Just this year, when asked

the same question, 48% of respondents stated that same-sex marriage should be

legal, and 44% stated that it should be illegal. There is an undeniable rise in

support for same-sex marriage; if the trend continues, there will be no other

time better to do research than the moment when opinions are basically tied.

Allport’s Contact Hypothesis

In 1954, Allport changed the landscape of psychology with his work on

prejudice, specifically his theory of contact hypothesis (Bowen & Bourgeois,

2001). He suggested that people become more accepting and less discriminatory of

a group of people once they actually know those people. In other words, more

familiarity and experience with a different group leads to better understanding

and less stereotypical thoughts. Past research has studied the effect of contact

with LGBT people before college (Bowen & Bourgeois, 2001). They found that

attitudes towards homosexuals improved drastically when they lived in the same

residence halls, took a class to familiarize themselves with the LGBT community,

or simply interacted with homosexuals in the classroom. This theory has been

used in reference to many different minority groups, specifically ethnic

minorities (Bowman, 2012) and it will be interesting to see how it relates to

sexual orientation minorities.

Cross-Cultural Background

Research relating to attitude formation toward the LGBT community is not

limited to the United States. In fact, many nations have conducted research

concerning this topic; two of the most relevant studies come from Turkey and

China. Cirakoglu (2006) found that college-aged students in Turkey applied

varying attitudes towards labels relating to the LGBT community, such as

“lesbian,” “gay,” or “homosexual.” MANOVA testing strongly suggested that

students’ attitudes were directly impacted by their gender, the label, and level

of contact. In addition, Cao, Wang, and Gao (2010) researched the correlation

between Chinese students’ perception of LGBT individuals and their attitudes

towards the LGBT community. Significant results indicated that there are

multiple independent variables which impact attitude, including perception, area

of study, and contact. These studies are representative of the world-wide

interest in the topic of attitude formation towards the LGBT community.

Relevancy

College students are relevant in this overarching discussion for reasons

more than that they are easy to sample. For instance, LGB college students are

impacted by the manner in which their peers and faculty treat them. Schmidt,

Miles, and Welsh sought to better understand the influence of homosexuality on

students’ college experience (2011). They found that college is different for

heterosexual students than it is for LGB students, as evidenced by the ways they

spend their time and the activities in which they participate. In addition,

their study strongly indicated that LGB students experience greater confusion on

career choices and that career confusion is strongly predicated on perceived

discrimination and social support. Also, college students serve as a unique

population because of their impact on professional LGBT individuals in one of

the safest working environments: the college campus. In other words, college

students’ attitudes towards the LGBT community have a direct impact on LGBT

professors on college campuses. Previous research indicates that college

students tend to view LGBT professors as biased (Anderson & Kanner, 2011). The

same study posited two cognitive structures that relate to this topic: subtle

prejudice and expectancy violation; both constructs were significantly supported

by the data collected in the study. Keeping in mind the unique role of college

students in the arena of attitude formation towards the LGBT community, this

paper seeks to understand the causes and influences during the process of

attitude formation.

Hypotheses and Operationalized Variables

The following independent variables will be measured by self-reported

test items: age, gender, ethnicity, number of close friends who identify as

LGBT, number of close family members who identify as LGBT, influence of parental

beliefs, similarity to parental beliefs, influence of friends’ beliefs, and

similarity to friends’ beliefs. The dependent variable (participant’s attitude

towards LGBT people) will be measured using the Lamar & Kite’s

Components of Attitudes Toward

Homosexuality measure (1998). The hypothesis states that college students at a

midwestern institution will base their attitude towards the LGBT community more

on their friends’ attitude of the LGBT community than on their mother’s attitude

or their father’s attitude.

Method

Participants

One hundred fifty one students from a midwestern university participated

in the study; they did not receive any class credit or reward of any kind. Data

from nine participants (one man, six women, and two that did not report their

gender) who reported that they were lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or

questioning were excluded from the analysis. Therefore, 142 participants’ data

are considered in the data analysis. Breakdown of the 142 who reported ethnicity

was as follows: 89.4% Caucasian, 7.0% African American, 1.4% Latino, and 2.1%

selected Other as their ethnicity. Breakdown of the 140 participants who

reported their age was as follows: 50% age 18-20, 40.8% age 21-24, and 7.9% age

25 and above. Data were collected in accordance with the ethical standards of

the American Psychological Association (American Psychological Association,

2010).

Materials

A 55-item questionnaire was compiled using questions from the Components

of Attitudes Toward Homosexuality scale (Lamar & Kite, 1998), as well as six new

items. The questionnaire used all the items on the Components of Attitudes

Toward Homosexuality scale, but each item was adjusted to include both “lesbians

and gay men” instead of focusing on one of the other group. Items included

statements such as, “Lesbians and gay men should be required to register with

the police department where they live,” “Gay men and lesbians are a viable part

of our society,” and “Most lesbians and gay men like to dress in opposite-sex

clothing” (Lamar & Kite, 1998). Of the 49 items on the Components of Attitudes

Toward Homosexuality scale, 15 were reverse-scored; all items scored so that a

higher number indicates more negative attitudes towards homosexuality. Three new

items measured self-reported levels of influence of the participant’s mothers,

fathers, and friends, with items such as “My beliefs/morals of homosexuality

have been influenced (either positively or negatively) by my mother’s beliefs.”

Another three original items measured self-reported levels of similarity to the

beliefs of the participant’s mother, father, and friends with items such as “My

beliefs/morals of homosexuality are similar to my mother’s beliefs.”

Procedure

Participants were asked to complete the 55-item questionnaire during

class time. The researcher explained the general goal of the study and

explicitly stated that the object of the study was not to judge anyone on their

opinions but to gain a better understanding of attitudes towards homosexuality.

Participants were also informed that they could withdraw from the study at any

time, if they became overly uncomfortable. Participants were informed verbally

and in written instruction that all responses were anonymous. The completion of

the survey took no longer than 15 minutes for the participants to complete.

After completion of the surveys, the experimenter debriefed the participants and

answered any questions regarding the research study.

Results

There were three independent variables (similarity to father, similarity

to mother, similarity to friends) and seven dependent variables (when

considering the total score and the 6 sub-scores). To test the hypothesis that a

person’s attitude towards LGB individuals differed due to their congruency with

their father’s opinion, a perceived congruency with father (low congruency,

medium congruency, high congruency) by attitude one-way ANOVA was performed.

Results indicated a significant difference in attitude based on

congruency with father, F (2,116) =

13.048, p < .001. Following this format, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was run

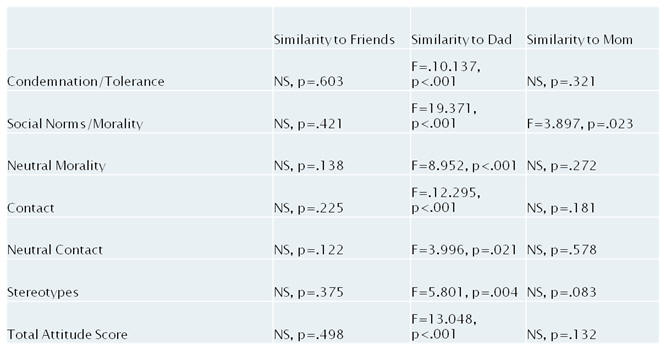

for each variable; specific results can be found in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1

Note: NS

= a non-significant result, F = the

ANOVA score, and p = probability.

Other Results: Correlations

A Pearson bivariate correlation was performed between gender (1 = men, 2

= women) and total attitude score (higher score indicates more negative

attitudes towards homosexuality).

This analysis indicated a negative correlation between gender (Mean

= 1.590 SD = .494) and total attitude score (Mean

= 93.308 , SD = 32.814), r (df = 139) = -.360,

p < .001. In other words, as gender increased, the total attitude score

decreased; women were more likely to have less negative feelings towards

homosexuality.

A Pearson bivariate correlation was performed between the number of close

friends who identify as LGBT and total attitude score (higher score indicates

more negative attitudes towards homosexuality).

This analysis indicated a negative correlation between the number of

close friends who identify as LGBT (Mean

= 2.204 SD = 3.405) and total attitude score (Mean

= 93.308 , SD = 32.814), r (df = 141) = -.382,

p < .001. In other words, as the number of close LGBT friends increased,

the total attitude score decreased; the more homosexual close friends a

participant had, the more likely they were to have less negative feelings

towards homosexuality.

A Pearson bivariate correlation was performed between the number of close family

members who identify as LGBT and total attitude score (higher score indicates

more negative attitudes towards homosexuality).

This analysis indicated a negative correlation between the number of

close family members who identify as LGBT (Mean

= .366 SD = .767) and total attitude score (Mean

= 93.308 , SD = 32.814), r (df = 141) = -.238,

p < .001. In other words, as the number of close LGBT friends increased,

the total attitude score decreased; the more homosexual family members a

participant had, the more likely they were to have less negative feelings

towards homosexuality.

Discussion

The original hypothesis stated: College students at a midwestern institution

will base their attitude towards the LGB community more on their friends’

attitude of the LGBT community than on their fathers’ beliefs or their mothers’

beliefs. Because there were no significant results for the friends variable (on

the composite score or any of the sub-scales), only one significant result for

the mother variable, and all significant results for the father variable, it is

clear that this data does not support the original hypothesis. Instead, it

appears as if college students at a midwestern institution will base their

attitude towards the LGB community more on their fathers’ attitude of the LGBT

community than on their friends’ beliefs or their mothers’ beliefs.

Limitations

If this study is repeated in the future, there are a few alterations that would

improve the quality of the results. First, the participants were verbally

informed of the scale direction and it was written on the white board of the

classroom, but at least two students’ surveys were not included because they

wrote the scale in the wrong direction at the top of their survey. In future

studies, the Likert scale should be included at the top of every page. Also, the

quality of the original survey questions can be improved. In the present survey,

participants were asked how similar their opinion of homosexuality was in

comparison to their fathers’ opinions, their mothers’ opinions, and their

friends’ opinions. Instead of asking participants to answer the question in that

self-report fashion, a more effective prompt would ask participants to answer a

Likert scale indicating their fathers’, mothers’, and friends’ support for

homosexuality.

Implications

In the future, this project can help further the search for the catalyst of

attitude formation towards the LGBT population. As stated earlier, after we

uncover the source of an attitude, we can delve into the details and the cause

of the source’s influence. Future research may include a population with more

variability in ethnicity, sexual orientation, and age. In a broad analysis, this

research further reveals the unanswered question: What is the origin of

individuals’ attitudes towards homosexuality? This work can also serve as the

starting block for research into the effects of attitude formation; it would be

interesting to look for patterns in the behavior of those who form their

attitudes in one way or another. At the end of the day, “Thoughts become

feelings, feelings become attitude, and attitude becomes behavior” (J.L. Kemp,

personal communication, September 24, 2012). It is this quest for understanding

that inspired this project and it is that same quest that will fuel similar

projects in the future.

References

Anderson, K.J., & Kanner, M. (2011). Inventing a gay agenda: Students’

perceptions of lesbian and gay professors.

Journal of applied Social Psychology,

41.

Blackwell, C. W. (2008). Nursing implications in the applications of conversion

therapies on gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender clients.

Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 29

(6), 651-655. doi:10.1080/01612840802048915

Bowman, N.A., & Griffin, T.M. (2012). Secondary transfer effects of interracial

contact: The moderating role of social status.

Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority

Psychology, 18 (1), 35-44. doi:10.1037/a0026745

Bowman, A.M., & Bourgeois, M.J. (2001). Attitudes toward lesbian, gay, and

bisexual college students: The contribution of pluralistic ignorance, dynamic

social impact, and contact theories.

Journal of American College Health, 50 (2), 35-44

Cao, H., Wang, P., Gao, Y. (2010). A survey of Chinese university students’

perceptions of attitudes towards homosexuality.

Social Behavior & Personality: An

international journal, 38 (6), 721-728. doi:10.2224/sbp.2010.38.6.721

Çirakoğlu, O. (2006). Perception of homosexuality among Turkish university

students: the roles of labels, gender, and prior contact.

Journal of Social Psychology, 146

(3), 293-305.

GLSEN. (2003). The 2003 national school climate survey: the school related

experiences of our nations’ lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth

Lamar, L. & Kite, M. (1998). Sex differences in attitudes toward gay men and

lesbians: A multidimensional perspective.

The Journal of Sex Research, 35 (2), 189-196

Reals, T. (2012, May 14). CBS News. Retrieved from

http://www.cbsnews.com/8301-503544_162-57433493-503544/ poll-most-americans-support-same-sex-unions/

Robin, L., Brener, N.D., Donahue, S.F., Hack, T., Hale, K., Goodenow, C. (2002)

Associations between health risk behaviors and opposite-, same-, and both-sex

sexual partners in representative samples of Vermont and Massachusetts high

school students. Archive of Pediatric and

Adolescent Medicine, 156 (4), 349-355

Sarantakos, S. (1998). Sex and power in same-sex couples.

Australian Journal of Social Issues,

33 (1), 17-36.

Schidlo, A., & Schroeder, M. (2002). Changing sexual orientation: A consumers’

report. Professional Psychology: Research

and Practice, 33 (3), 249-259. doi:10.1037//0735-7028.33.3.249

Schmidt, C.K., Miles, J.R., Welsh, A.C. (2011). Perceived discrimination and

social support: The influences on career development and college adjustment of

LGBT college students. Journal of Career

Development, 38 (293). doi:10.1177/0894845310372615

Stark, C. (2012, May 12). CNN Library. Retrieved from

http://www.cnn.com/2012/05/11/politics/btn-same-sex-marriage/index.html