The Correlation between Use of Common Drugs and Depression Symptoms

Sarah L. Adams

Abstract

Since many common drugs such as caffeine and alcohol are psychoactive in nature, there may be a tendency for habitual users of such substances to experience more dramatic changes in mood than those who do not use them frequently. For this study, the researcher investigated the possibility of a correlation between drug use and mood symptoms typically associated with clinical depression. The participants, a convenience sample of approximately 100 students from a small, midwestern university, completed a short survey relating to drug use and depression-like feelings. The survey featured a self-report scale indicating agreement with a particular statement or frequency of personal events e.g. intense sadness. The results suggested that individuals who reported regular use of common psychoactive drugs (caffeine in particular) were more likely to indicate occurrence of depression-related effects. The study findings may be useful in investigating the chemical factors in the brain that contribute to clinical depression.

Keywords: Depression, drugs, psychoactive

Every year, millions of citizens in the United States suffer from the effects of clinical depression and/or its associated symptoms. The DSM IV criteria for defining a major depressive episode include depressed mood and/or loss of interest or pleasure accompanied by any five or more other descriptive factors such as fatigue, thoughts of death, feelings of worthlessness, etc. Major depressive disorder is described as separate, recurrent episode events (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Also, the modern lifestyle of many Americans exposes them daily to a number of common, psychoactive drugs such as caffeine, alcohol and marijuana. These substances are often used (or abused) for their calm-inducing, stimulant or otherwise mind-altering qualities. Psychoactive drugs act upon and change the brain�s neurochemistry, producing the �high� or �buzz� effects that many users seek. However, clinical depression is also associated with chemical changes in neurotransmitter levels within the brain (sometimes in combination with personal conflict or other sources of distress in a particular individual�s life). Since depression symptoms are connected with imbalances in brain chemistry, the presence of psychoactive drugs may be linked with an individual person�s likelihood of experiencing those symptoms at some point in life.

According to a recent analysis of data on the presence of depression in the United States, the disorder affects over 21 million American children and adults each year. It is often concurrent with other serious, ongoing medical illnesses such as cancer and heart disease (Ranking America�s Mental Health, 2011). The same study indicates that depression is responsible for approximately $31 billion in lost productive time among American workers and is a primary factor in over 30,000 cases of suicide annually, particularly in the age range of 15-24 years (Ranking America�s Mental Health, 2011). These statistics suggest that clinical depression is a serious detriment to the overall health and wellbeing of United States citizens. Furthermore, habitual abuse of legal and illegal drugs continues to be an issue associated with social problems such as drunk driving, secondhand smoking and accidental death from drug overdose. Since depression and drug use are both serious societal issues and share a common dimension (effects on brain chemistry), it may be worthwhile to investigate the potential correlation between the two.

Depression has been associated with neurochemical changes in the brain for some time. Sigmund Freud once commented that he believed science would eventually describe the physiochemical effects of psychological events in detail, although the groundwork for such studies had not yet been laid when he was doing his research (Gilbert, 1984). Since the late 1950s and 1960s, researchers have been putting together information relating depression to catecholamines and the neurotransmitters known as monoamines (includes dopamine, norepinephrine and 5-HT). Major antidepressants, monoamine-oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and tricyclic compounds, generally act on the synaptic mechanisms for these neurotransmitters (Gilbert, 1984). Drugs that are subject to common abuse also tend to target the same neurotransmitters (Rudnick, 1998). The observed physiochemical effects for different drugs range widely; for instance, cocaine is known to block certain neurotransmitter transporters while amphetamines cause neurotransmitter release (Rudnick, 1998). Careful research is needed to establish the potential interaction of drugs and depression since an imbalance in a common neurotransmitter caused by one of the two factors could have an impact on the other.

Caffeine

Fredholm, B�ttig, Holm�n, Nehlig and Zvartau (1999) stated that the primary action of caffeine in the brain is that of an adenosine receptor antagonist. However, they also noted that other behavioral experiments may indicate other functional mechanisms. Caffeine is recognized as an increase factor for dopaminergic transmission, an interesting point considering that amphetamines and cocaine cause the release of dopamine. With regard to behavioral observations, caffeine appears to have an initial stimulant effect in humans but seems to lead to a delayed behavioral depression when applied in high doses to experimental animals. For humans, high doses of caffeine are also associated with increased anxiety symptoms, though individuals with anxiety due to depression do not seem to exhibit unusual sensitivity to caffeine (Fredholm, et al. 1999).

One early psychological study investigating a link between depression and caffeine consumption indicated a positive correlation between caffeine and both depression and anxiety symptoms (Veleber & Templer, 1984). The experimenters administered a Multiple Affect Checklist (self-report) to volunteer participants both before and one hour after a double-blind dosage of either 150 mg or 300 mg of caffeine. They found that dose level appeared to be a significant predictor for anxiety at the .001 level and for heightened hostility and depression at the .01 level. In addition, the research included covariate analysis of gender, age and occupation; the results indicated that gender (males having higher scores) was a significant predictor for posttest depression and hostility at the .01 level but found no relation of the other two variables to experimental measures. In the discussion of the project, the researchers noted that since caffeine is associated with a more �delayed� effect with regard to depressive symptomology, they may have observed more anxiety if the posttest had been administered sooner following caffeine intake (Veleber & Templer, 1984).

Other studies place more of a principle focus upon the involvement of anxiety disorders in any correlation between depression and caffeine. Luebbe and Bell (2009) conducted an experiment with sets of 5th and 10th grade children to investigate parameters of intake and subsequent negative effects of caffeine in these age groups. The students self-reported their caffeine intake, gave height/weight information and completed a Likert scale inventory to assess any symptomology associated with the drug. The study was undertaken in response to other reports of caffeine-related physical dependence and withdrawal evidence in children. The researchers found a positive correlation between depression and caffeine intake in both age groups. Both had also exhibited a positive relation between weekly intake and other subjective effects with the exception of stimulation. In teens, depression and reported withdrawal effects were related as well as anxiety and stimulation. From their data, the experimenters concluded that most children and teens experience little restriction regarding caffeine consumption and that higher intake appears to put youth at an increased risk for depressive symptomology (Lubbe & Bell, 2009).

A related 2008 study examined similar qualities but also included the parameter of sleep (Whalen, Silk, Semel, Forbes, Ryan, Axelson, Birmaher & Dahl). Their experiments assessed relationships among sleep quality, caffeine intake and affect using two groups of youth: one that was comprised of individuals with major depressive disorder (MDD) and one group of healthy controls (no history of mental diagnosis). The participants self-reported caffeine use, quality of sleep and feelings/behaviors (affect) over a period of eight weeks during which the MDD group received depression treatment. The researchers hypothesized that the experimental group would experience an increase in sleep quality and a decrease in caffeine use over the treatment period. Youth with MDD reported more caffeine use and sleep problems as well as more anxiety on days they consumed caffeine relative to healthy youth. Caffeine/sleep analysis yielded only a connection between caffeine use in a given day and number of nighttime awakenings the following night. Caffeine/negative affect analysis yielded only a connection between caffeine and feelings of nervousness (not anger, sadness or upset). The experimenters noted that children with MDD and comorbid anxiety reported higher caffeine intake than any other participants. Since the MDD group�s caffeine use decreased but sleep quality did not improve significantly during the treatment, the experiment suggests that youth with MDD may use caffeine to self-medicate for depression symptoms (Whalen, et al. 2008).

Alcohol

With regard to alcohol and depression, some studies similarly include several other factors that may interact with the drug and behavioral effects. Dennhardt and Murphy (2011) performed research exploring racial differences (European-American vs. African-American) in depression, distress tolerance, delay discounting and alcohol-related problems. Hypotheses included the projection that high levels of delay discounting and depression and low levels of distress tolerance would be associated with more alcohol problems, and specifically with more dependence-related symptoms (impaired control over drinking and physical dependence). Depression and distress tolerance were assessed with self-report scales, drinking with a questionnaire and delay discounting using preference questions. The experimenters found that European-American students showed a correlation between depression and physical dependence, African-American students showed an association between depression and impaired control/physical dependence and both races showed a significant relationship between depression and alcohol problems. They suggested that drinking may be associated with distress tolerance in African-American students because they are likely to encounter more discrimination and hardship in college than European-Americans (Dennhardt & Murphy, 2011).

Another study considered whether participants� dispositions to rash action moderate the effects of concurrent alcohol use or depressive symptoms on alcohol problems (King, Karyadi, Luk & Patock-Peckham, 2011). The basis for the research was the idea that impulsivity (a core personality trait) may increase an individual�s vulnerability to both alcohol use disorders and use of alcohol as a coping method for dealing with feelings of depression. 573 participants self-reported on impulsivity, alcohol use and depression symptom measures. The researchers found that lower levels of premeditation enhanced the association between depressive symptoms and alcohol problems, while lower perseverance and higher sensation seeking were related to more alcohol problems at higher levels of alcohol use. Their findings suggested that feelings of negative urgency may be directly related to alcohol problems while premeditation, perseverance and sensation seeking qualities are indirectly related by modifying the relations between depressive symptoms/alcohol use and alcohol problems (King, Karyadi, Luk & Patock-Peckham, 2011).

Other work has taken a more biological view of the association between alcohol and depression. Stevenson, Schroeder, Nixon, Besheer, Crews and Hodge (2009) conducted an experiment wherein the researchers used mice to investigate whether alcohol exposure and subsequent abstinence contributes to depression-like behavior and decreased hippocampal neurogenesis. Groups of mice were allowed to drink alcohol-water and tested for depression symptoms using a forced swim test. One group was given the antidepressant desipramine. Brain changes were assessed through immunohistochemistry. Alcohol group mice showed a significant increase in depression behavior 14 days after abstinence and also showed a significant but temporary increase in anxiety behavior after one day of abstinence which was gone by 15 days. In addition, desipramine treatment reduced immobility and depression behavior in mice when administered during the 14 days of abstinence. The researchers also observed a decrease in the number of neural progenitor cells (NPCs) in the dentate gyrus of the brains of alcohol group mice. The results of the study supported the hypothesis that alcohol affects molecular pathways in the brain that are also associated with the pathophysiology of depression; they also indicated that antidepressant treatment may alleviate some of pathological neurobehavioral adaptations of alcohol abstinence (Stevenson, et. al. 2009).

However, another study on methods of measurement could influence how the results of many others are viewed. Graham, Massak, Demers and Rehm (2007) investigated how different ways of assessing alcohol use and depression symptoms could produce varying research results. Alcohol use was judged in four ways (frequency, volume, quantity per occasion and heavy episodic drinking) and two types of depression assessment were used (clinical method of diagnosing major depressive disorder and basic depressed affect). The sample size for this study was very large; over 14,000 participants were evaluated via phone interview. The researchers found that gender and method of measurement did indeed produce significantly different results when searching for a link between alcohol and depression. From the data gathered, they determined that studies using heavy drinking per occasion as the standard of alcohol use found more significant relationships to depression than those using frequency or volume of alcohol consumed overall. In addition, the alcohol-depression connection appeared to be stronger for women than for men only when depression was assessed based on clinical criteria rather than affect. The researchers noted that future studies may benefit from separate gender analyses and more focus on episodic binge drinking when searching for significant associations (Graham, Massak, Demers & Rehm, 2007).

Marijuana & Tobacco

It is not that unusual for a particular individual to use caffeine or alcohol alone on a regular basis while exposing themselves to no other psychoactive drugs. However, drugs such as marijuana are often used concurrently with tobacco or other more illicit substances. Bonn-Miller, Zvolensky and Johnson (2010) conducted a study to examine uni-morbid and co-occurring tobacco and marijuana use in relation to the negative emotional symptoms of anxiety and depression. 250 participants were divided into four groups: tobacco use only, marijuana use only, concurrent use of both drugs and use of neither drug. The researchers administered questionnaires regarding frequency of smoking, frequency of marijuana use and mood/anxiety (an assessment of alcohol use was also included). The results of the study indicated that people who use tobacco alone experience higher levels of depression symptoms and more negative affect than other groups while the combined drug group reported the highest levels of anxiety. In addition, the two groups that included marijuana use were associated with greater use of alcohol than the tobacco or drug-free groups. The experimenters concluded that those who use tobacco alone may be more subject to depression than users of other drugs or non-drug users (Bonn-Miller, Zvolensky & Johnson, 2010).

Another study investigated the effects of marijuana and MDMA (ecstasy) on major depression; it also searched for gender differences with stratification studies (Durdle, 2008). The researchers assessed 226 participants using the DSM Structured Clinical Interview for depression and a drug use questionnaire. They also considered whether or not marijuana use met the criteria for a DSM-defined lifetime disorder. The results yielded a significant correlation between marijuana use disorder and major depressive disorder (MDD) but no similar relationship between ecstasy and MDD. Use of ecstasy and marijuana were not significantly associated with each other. Separate gender analysis produced a significant correlation between combined marijuana use disorder and ecstasy use with MDD in females, but found no similar correlation for males. The experimenters theorized that the difference in females could be due to marijuana effects in the female 5-HT system that manifest as depression or a dose-specific relationship between ecstasy and MDD (females would be more susceptible due to lower body weight). In addition, the findings suggested that marijuana use may be a confounding variable in studies that indicate a definite relationship between ecstasy and MDD (Durdle, 2008).

With regard to marijuana and depression, motive for use of the drug may act as a confounding variable in any correlational study, a problem that Bonn-Miller, Zvolensky, Bernstein and Stickle (2008) sought to address. 149 participants completed the Marijuana Motives Measure Test as well as questionnaires regarding mood/anxiety and agoraphobia (an alcohol questionnaire was also included). The researchers posited that frequent use of marijuana and coping motive would be more predictive of anxiety and mood problems. They covaried factors such as alcohol use and total years of marijuana use and discovered that frequency of marijuana use (past 30 days) and presence of coping motives reliably predicted anxious arousal symptoms, agoraphobic cognitions, and worry. In addition, daily tobacco use was significantly correlated with anxiety, worry, agoraphobic cognitions and anhedonia. The experimenters concluded that it is important to consider motive for drug use when examining the relationship between marijuana and anxiety/depression (Bonn-Miller, et al. 2008).

Another particularly thorough study attempted to find a causal relationship between marijuana and depression (Harder, Morral & Arkes, 2006). The researchers attempted to determine whether marijuana use predicts later development of depression after accounting for differences between users and non-users of marijuana and hypothesized that ongoing marijuana use is an independent predictor of depression in adults. The longitudinal study began in 1984; respondents were asked about their frequency and duration of marijuana use with follow-up assessments made in 1988, 1992, 1994 and 1998. During the 1992, 1994 and 2002 interviews, respondents were also asked about their mood within the past week. Factors such as age, race and socioeconomic status were used as baseline covariates. The researchers also employed two experimental models; one consisted of individuals who had used marijuana during the past year and one included a four-year time lag. After adjusting for differences in baseline risk factors of marijuana use and depression, past-year marijuana use did not significantly predict later development of depression. Odds of depression for past marijuana users was reported to be only 1.1 times higher than odds for non-marijuana users (Harder, Morral & Arkes 2006).

Other Drugs

�Harder� illicit drugs such as cocaine and ecstasy have also been examined with relation to depressive symptomology. Rubin, Aharonovich, Bisaga, Levin, Raby and Nunes (2007) investigated the interaction of comorbid major depression with abstinence effects in cocaine users; the researcher posited that cocaine users who also suffer from MDD will experience more severe withdrawal effects than those with no history of MDD. Participants were divided into cocaine-dependent and cocaine-dependent with MDD groups and assessed using the Beck Depression Index (BDI) and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Results indicated that individuals with cocaine dependence and MDD had significantly higher BDI scores during abstinence than those with cocaine dependence alone. There appeared to be no relationship between abstinence and anxiety over three days, but researchers noted a correlation between anxiety and years of drug use. The experimenters concluded that monitored abstinence for cocaine users may help distinguish between withdrawal and actual depression and that the sustained dysphoria experienced by MDD patients may be related to drug-induced changes in the brain (Rubin, et al. 2007).

Another study examined the relationship between former chronic use of ecstasy (chronic use defined as 100 lifetime exposures or more) and elevated depression scores (MacInnes, Handley & Harding, 2001). 29 participants reported former ecstasy use, depression using the BDI and daily life hassles/stress. Levels of depression were significantly elevated compared to a matched non-drug using control group; frequent but mild life stress and number of ecstasy tablets consumed in a 12-hour period were the only significant predictors of depression ratings in the experimental group. Levels of depression were not significantly impacted by reports of alcohol, amphetamines or any other type of psychoactive drug assessed in the study. The researchers concluded that binge consumption of ecstasy appears to have a significant relationship to depression ratings, which suggests a rationale for a biological basis for depression reported by ecstasy users (MacInnes, Handley & Harding, 2001).

A related experiment investigated the ecstasy-depression correlation while specifically controlling for concurrent use of other drugs (Roiser & Sahakian, 2003). The basis for the study was observed damage to serotonin neurons in the brains of laboratory animals that were treated with ecstasy. Participants were 30 current ecstasy users, 30 poly-drug controls who had never used ecstasy, 30 drug-na�ve controls with no history of illicit drug use and 20 past ecstasy users. Current and past ecstasy users scored significantly higher on the BDI than non-drug users but were not significantly different from the poly-drug group. Participants were also given an affective test to determine whether ecstasy users show the same kind of attention bias toward negatively-toned material as depressed people; this section of the study found no significant similarity. Overall, the research indicated that previously observed correlations between ecstasy use and depression may be confounded by use of other psychoactive drugs (Roiser & Sahakian, 2003).

In addition to illegal drugs, researchers have investigated the relationships of depression to therapeutic drugs such as Ritalin. One study examined the effects of Ritalin in depressed individuals to differentiate between pharmacological effects and its effects on target symptoms (Kerenyi, Koranyi & Sarwer-Foner, 1960). 159 participants were divided into two groups, one of which was assessed in psychiatric treatment clinics and the other in private practices. Lab tests and reported changes in weight, sleep, eating, etc. were used to assess the physiological effects of the drug. 81% of cases showed reported improvement in mood and 62% showed increased psychomotor activity such as speech in psychotherapy sessions. Patients with depression responded better than those with schizophrenia or other illnesses with depression symptoms. The research indicated that Ritalin may be useful in treatment of depression due to its effect of giving a little more energy to the patient with which he/she can better communicate with a therapist or doctor. It appeared less effective with administered without or with little therapeutic interaction. The researchers concluded that Ritalin may be useful in treatment of depressive symptoms as long as it is applied to the right patients with proper therapeutic support (Kerenyi, Koranyi & Sarwer-Foner, 1960).

Another study employed a general drug-using population to determine how combinations of psychoactive substance use, personality, psychosocial and negative life events affect risk for developing depressive symptoms (Buckner & Mandell, 1990). The research involved a short-term longitudinal study wherein participants who reported depressed symptoms at time 2 but not time 1 were defined as experimental �cases� and others used as �controls�. Researchers assessed drug use, negative life events and social supports; the investigated factors were found to be significantly related to depression symptoms in drug users. Of the drugs investigated, methaqualone (a synthetic central nervous system depressant compound that is similar to barbiturates) appeared to show the most specific and significant relationship to depression independent of self-esteem ratings or negative events. Heroin also showed significant prediction value for depressive episodes, but lost it when adjusted for social/life event factors. The researchers also cited another study that found evidence supporting the theory that methaqualone could be an antecedent to depression rather than a consequence (Buckner & Mandell, 1990).

Research Hypotheses

Many past studies investigating a connection between drug use and depression have found statistically significant results of some kind. Several of these research projects have included a biological basis for the correlation; the chemical or physical changes in the brain brought about by one of the factors may have an impact on the presence or intensity of the other. The current study hypothesizes that individuals who report high levels of drug use on a short, self-report survey will also be more likely to report frequent occurrences of depressive symptomology. Also, since many of the reviewed studies included some evidence that observed effects of these conditions vary based on gender, this project will investigate differences in response for males and females. All variables will be operationalized as survey responses given by participants.

Method

Participants

Study participants were a convenience sample of undergraduate students from a small, rurally located, midwestern university. They were approached at the beginning of classes and asked to fill out a voluntary, anonymous survey. Classes surveyed included two introductory psychology classes, one introductory biology class and one upper level adult psychology class. A total of 100 students participated, but only 96 returned usable surveys. The only demographic requested other than gender was year in school. Out of 96 participants, 50 were male, 42 were first year students, 22 sophomores, 17 juniors, 12 seniors and 3 fifth year students or above.

Materials

The survey distributed was designed by the researcher and included two demographic questions, 11 drug analysis questions and 14 questions to assess depressive symptomology (Appendix B). Responses for all non-demographic questions were given on a six-point Likert type scale or a yes/no option. All participants received the same survey (balanced research) and the direction of several questions was reversed to eliminate potential effects of yea/naysaying. Participants were given contact information for the researcher and school counselors and asked to initial a consent slip. Consent slips were returned separately from surveys (See Appendix A). Participants were informed before taking the survey that it was optional and had no impact upon class grades. A total of 100 surveys were distributed, but four were eliminated from the study based on insufficient responses (each of the four was missing an entire page of answers). However, the number of unusable surveys was relatively small and unlikely to have a negative effect on study results.

Procedure

The researcher created an initial draft of the survey which was then field tested and revised before submission to the McKendree University Institutional Review Board (IRB) with a request for expedited review. The IRB approved the revised survey and found no ethical problems with the proposed study. The surveys were then distributed and data was analyzed using SPSS 14.0 software. The relationship between drugs (both individual types and overall) and depression was examined using a Pearson�s Correlation test, gender differences using a two-tailed independent samples t-test and variations in drug use/depression by year in school using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). ANOVA tests included Scheffe, Tukey (Honestly Significant Difference) and Fisher (Least Significant Difference) measures.

Results

To test the hypothesis that higher reported drug use will be related to higher reported depression symptoms, the Pearson Correlation test of overall drug use (M=19.86, SD=4.77) and depression symptoms (M=31.89, SD=10.15) showed a significant positive relationship, r=.27, p=.008. Analysis of the correlation between depression and individual drug types yielded no significant findings with the exception of caffeine, r=.06, p=.045. Analysis of depression and the �other drugs� category (other narcotics that were not caffeine, alcohol, tobacco or marijuana) could not be assessed because all survey responses to the question regarding them were equal to 1 (No use). Mean values for responses regarding use of each individual drug type are shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Mean Values of Responses to Drug Use Questions

Note. Possible range for responses to tobacco, marijuana, other psychoactive drugs and alcohol score = 1 to 7. Possible range for total caffeine score = 4 to 24.

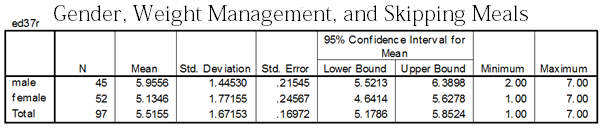

To assess gender variation in reported depression symptoms, the independent samples t-test comparing male and female depression scores found no significant differences between male (M=31.40, SD=9.57) and female responses (M=32.39, SD=10.78), t(94)=-.48, p=.64. To assess gender variation in reported drug use, the independent samples t-test for comparing male and female drug scores also did not find any significant differences between males (M=19.90, SD=4.82) and females (M=19.83, SD=4.76), t(94)=.06, p=.95.

To investigate variation of drug use reports among years in school, the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) of drug use of first years (M=19.19, SD=3.95), second years (M=18.82, SD=4.43), third years (M-21.53, SD=5.87), fourth years (M=20.67, SD=4.85), fifth years and up (M=24.33, SD=8.33) indicated no significant differences, F (4, 91)=1.80, p=.14.

To investigate variation of depression symptoms among years in school, the ANOVA test comparing depression score of first year (M=30.70, SD=9.24), second years (M=29.95, SD=8.39), third years (M=37.41, SD=12.16), fourth years (M=30.83, SD=11.18), fifth years and up (M=35.67, SD=13.78) produced no significant results, F (4, 91)=1.79, p=.14. Mean total responses to depression questions are plotted for each year in Table 2. The post hoc testing using Fisher�s LSD test for variation of depression symptoms among years in school indicated significant differences between first year students and third year students, p=.022 as well as between second year students and third year students, p=.023. However, since the ANOVA and more conservative post hoc tests (Scheffe, Tukey) did not produce significant results, this finding is likely negligible.

Table 2

Mean Total Depression Scores by Year in School

Note. Possible range for depression score total was 16 to 92.

Discussion

The data gathered and analyzed in this study appear to support the hypothesis that there could be a positive correlation between reported depression symptoms and drug use. However, the relationship observed does not indicate directional correlation, so further investigation into causation factors may be useful. The overall association between the two factors corresponded to prior evidence reported by Buckner and Mandell (1990). The earlier research included analysis of negative life events and social distress, which may be a useful addition to an improved study. The present research also found results consistent with the significant relationship between depression and caffeine indicated in previous studies (Veleber & Templer, 1984; Lubbe & Bell, 2009). The even numbers of male and female participants lend strength to the finding that gender may not be significantly related to depression or drug use. However, the high number of first-year students compared to upperclassmen may have unbalanced the findings for the same relationships among years in school.

Since the participants indicated no use of �harder� drugs such as ecstasy or heroin, this study provides no evidence to support findings such as the connection between binge consumption of ecstasy and depression reported by MacInnes, Handley and Harding (2001). In addition, this study found no significant relationship between marijuana and depression, which supports other evidence that marijuana is either unrelated to depression or related primarily by motive for use of the drug (Bonn-Miller, et al. 2008; Harder, Morral & Arkes 2006). In the case of alcohol, this research found no significant results, but assessed use of the drug only by frequency of drinking alcoholic beverages. Previous research by Graham, Massak, Demers and Rehm (2007) posits that the depression/alcohol relationship appears more significant when measured by occasions of binge drinking, so an improved study may include further inquiry into the nature of participants� alcohol use.

Since the present research was conducted using only a small convenience sample of participants from a private, midwestern university, larger samples of non-student populations or from other geographical areas would be helpful for comparison. In addition, the treatment of the subject was rather broad in that the survey distributed included questions regarding several different types of drugs. More useful and significant results may be obtained with more focused studies pertaining to each individual substance. Also, it is difficult to gauge causation using only a survey study. If future research can pinpoint particular chemical relationships, more controlled, experimental-style studies would likely provide information that is more useful for the purpose of developing treatments for depression.

In particular, the strong correlation observed between caffeine and depression warrants further investigation. Since college students are often thought to be vulnerable to stress and depression as well as be more likely to use large amounts of caffeine, it may be helpful to report more data about the relationship between those factors. The original premise of this research included the idea that psychoactive drugs and depression may be related on the basis of similar effects upon the brain. Since caffeine use ratings demonstrated the strongest and most significant connection to depression symptoms, continued research may be best directed toward investigation of caffeine�s action within the brain. Future studies may also examine the possibility of caffeine use as a self-treatment for feelings associated with depression.

Author�s Note

This research was conducted by Sarah L. Adams, McKendree University. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Sarah Adams, 610 Lila Court, New Baden, IL 62265 or by email: [email protected] or phone: 618-514-4286.

References

American Psychiatric Association. 1994. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Bonn-Miller, M., Zvolensky, M., Bernstein, A., & Stickle, T. (2008). Marijuana coping motives interact with marijuana use frequency to predict anxious arousal, panic related catastrophic thinking, and worry among current marijuana users. Depression And Anxiety, 25(10), 862-873. doi:10.1002/da.20370

Bonn-Miller, M., Zvolensky, M., & Johnson, K. (2010). Uni-morbid and co-occurring marijuana and tobacco use: examination of concurrent associations with negative mood states. Journal Of Addictive Diseases, 29(1), 68-77. doi:10.1080/10550880903435996

Buckner, J., & Mandell, W. (1990). Risk factors for depressive symptomatology in a drug using population. American Journal Of Public Health, 80(5), 580-585.

Dennhardt, A. A., & Murphy, J. G. (2011). Associations between depression, distress tolerance, delay discounting, and alcohol-related problems in European American and African American college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, doi:10.1037/a0025807

Durdle, H., Lundahl, L., Johanson, C., & Tancer, M. (2008). Major depression: the relative contribution of gender, MDMA, and cannabis use. Depression And Anxiety, 25(3), 241-247. doi:10.1002/da.20297

Fredholm, B. B., Battig, K., Holmen, J., Nehlig, A., & Zvartau, E. E. (1999). Actions of caffeine in the brain with special reference to factors that contribute to its widespread use. Pharmacological Reviews, 51(1), 99-100.

Gilbert, P. (1984). Depression: from psychology to brain state. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Graham, K., Massak, A., Demers, A., & Rehm, J. (2007). Does the association between alcohol consumption and depression depend on how they are measured? Alcoholism, Clinical And Experimental Research, 31(1), 78-88. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00274.x

Harder, V., Morral, A., & Arkes, J. (2006). Marijuana use and depression among adults: Testing for causal associations. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 101(10), 1463-1472. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01545.x

Kerenyi, A., Koranyi, E., & Sarwer-Foner, G. (1960). Depressive states and drugs. III. Use of methylphenidate (Ritalin) in open psychiatric settings and in office practice. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 831249-1254.

King, K. M., Karyadi, K. A., Luk, J. W., & Patock-Peckham, J. A. (2011). Dispositions to rash action moderate the associations between concurrent drinking, depressive symptoms, and alcohol problems during emerging adulthood. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 25(3), 446-454. doi:10.1037/a0023777

Lucas, M., Mirzaei, F., Pan, A., Okereke, O., Willett, W., O'Reilly, E., & ... Ascherio, A. (2011). Coffee, caffeine, and risk of depression among women. Archives Of Internal Medicine, 171(17), 1571-1578.

Luebbe, A., & Bell, D. (2009). Mountain Dew or mountain don't?: a pilot investigation of caffeine use parameters and relations to depression and anxiety symptoms in 5th- and 10th-grade students. The Journal of School Health, 79(8), 380-387.

MacInnes, N. N., Handley, S. L., & Harding, G. A. (2001). Former chronic methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA or ecstasy) users report mild depressive symptoms. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 15(3), 181-186. doi:10.1177/026988110101500310.

Ranking America�s mental health: an analysis of depression across the states. (2011). Retrieved October 25, 2011 from Mental Health America

Roiser, J., & Sahakian, B. (2004). Relationship between ecstasy use and depression: a study controlling for poly-drug use.Psychopharmacology, 173(3-4), 411-417. doi:10.1007/s00213-003-1705-6

Rudnik, G. (1998). Transporter structure and function. In B.K. Madras et al. (Ed.), Cell biology of addiction. (pp. 159-178). New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

Rubin, E., Aharonovich, E., Bisaga, A., Levin, F., Raby, W., & Nunes, E. (2007). Early abstinence in cocaine dependence: influence of comorbid major depression. The American Journal On Addictions / American Academy Of Psychiatrists In Alcoholism And Addictions, 16(4), 283-290. doi:10.1080/10550490701389880

Stevenson, J., Schroeder, J., Nixon, K., Besheer, J., Crews, F., & Hodge, C. (2009). Abstinence following alcohol drinking produces depression-like behavior and reduced hippocampal neurogenesis in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology: Official Publication Of The American College Of Neuropsychopharmacology, 34(5), 1209-1222.

Whalen, D. J., Silk, J. S., Semel, M., Forbes, E. E., Ryan, N. D., Axelson, D. A., & Dahl, R. E. (2008). Caffeine consumption, sleep, and affect in the natural environments of depressed youth and healthy controls. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 33(4), 358-367. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsm086.

Veleber, D. M., & Templer, D. I. (1984). Effects of caffeine on anxiety and depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 93(1), 120-122. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.93.1.120

Appendices

Appendix A: Consent Form

Read this consent form. If you have any questions, ask the experimenter and he/she will answer your questions

�I have read the above statement and have been fully advised of the procedures to be used in this project. I have been given sufficient opportunity to ask questions I had concerning the procedures and possible risks involved. I understand the potential risks involved and I assume them voluntarily.�

Please sign your initials, detach below the dotted line and continue with the survey.

Sign your initials here_________________ Date_________________

The McKendree University Psychology Department supports the practice of protection for human participants participating in research and related activities. The following information is provided so that you can decide whether you wish to participate in the present study. Your participation in this study is completely voluntary. You should be aware that even if you agree to participate, you are free to withdraw at any time, and that if you do withdraw from the study, your grade in this class will not be affected in any way. This survey is being conducted to assist the researcher in fulfilling a partial requirement for PSY 496W.

You must be over 18 years of age to participate in the survey. It should not take more than 10 minutes for you to complete and will be completely anonymous. If you should have any other questions, don�t hesitate to contact me, Sarah Adams 618-514-4286 or at [email protected] or Dr. Murella Bosse, 618-537-6882 or at [email protected]. Some of the questions in the survey may confront sensitive topics. If answering any of these questions causes you problems or concerns, please contact one of our campus psychologists, Bob Clipper or Amy Champion, at 537-6503.

Appendix B: Survey

Student Survey

1. Please indicate your gender. M F

2. Please indicate your year in school.

First Second Third Fourth Fifth+

For questions 3-13, please choose a response describing yourself from 1 (Never) to 6 (Very frequently).

3. I drink caffeinated soft drinks.

Never 1 2 3 4 5 6 Frequently

4. I drink energy drinks.

Never 1 2 3 4 5 6 Frequently

5. I smoke cigarettes.

Never 1 2 3 4 5 6 Frequently

6. I drink caffeinated coffee.

Never 1 2 3 4 5 6 Frequently

7. I use energy/caffeine pills.

Never 1 2 3 4 5 6 Frequently

8. I feel worthless or hopeless

Never 1 2 3 4 5 6 Frequently

9. I have trouble sleeping.

Never 1 2 3 4 5 6 Frequently

10. I have trouble staying awake.

Never 1 2 3 4 5 6 Frequently

11. I smoke marijuana.

Never 1 2 3 4 5 6 Frequently

12. I use other psychoactive drugs (cocaine, heroin, ecstasy, etc.)

Never 1 2 3 4 5 6 Frequently

13. I drink alcoholic beverages.

Never 1 2 3 4 5 6 Frequently

For questions 14-25, please choose a response describing yourself from 1 (Disagree) to 6 (Agree)

14. I have strong feelings of sadness.

Disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 Agree

15. I often worry unnecessarily.

Disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 Agree

16. I am energetic during the day.

Disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 Agree

17. Facing difficult and/or unfamiliar tasks causes me to panic.

Disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 Agree

18. I get frustrated quickly.

Disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 Agree

19. I look forward to spending time with friends.

Disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 Agree

20. I have high self-esteem.

Disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 Agree

21. I try to take care to eat healthy foods.

Disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 Agree

22. I cry or want to cry often.

Disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 Agree

23. I laugh a lot.

Disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 Agree

24. I enjoy my daily life.

Disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 Agree

25. I have experienced a loss of interest in things I used to enjoy.

Disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 Agree

For questions 26 and 27, please answer Yes or No

26. I take/have taken Ritalin, Adderall or similar medication.

Yes No

27. I take/have taken medication for symptoms of clinical depression.

Yes No

Thank you for completing this survey!

©